The operator of the stricken Fukushima

nuclear plant has been dumping something like a

thousand tons per day of radioactive water into the

Pacific ocean.

The whole complex is

leaking like a sieve, and the rivers of water pumped into the

reactors every day are just

pouring into the ocean (with only a slight delay).

Most people assume that the ocean will

dilute the radiation from Fukushima enough that any radiation reaching the West

Coast of the U.S. will be low.

For example, the Congressional Research

Service

wrote in April:

Scientists have stated that radiation in the ocean very quickly

becomes diluted and would not be a problem beyond the coast of Japan.

***

U.S. fisheries are unlikely to be affected because radioactive

material that enters the marine environment would be greatly diluted before

reaching U.S. fishing grounds.

And a Woods Hole oceanographer

said:

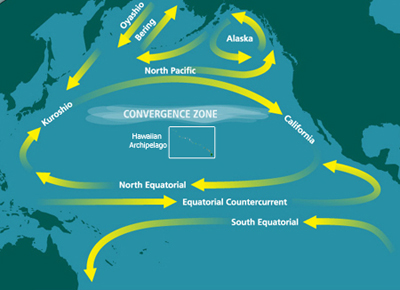

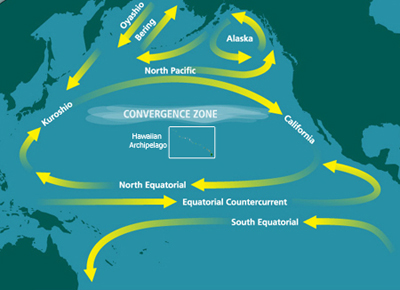

“The Kuroshio current is considered like the Gulf Stream of the

Pacific, a very large current that can rapidly carry the radioactivity into the

interior” of the ocean, Buesseler said.

“But it also dilutes along the way, causing a lot of mixing and

decreasing radioactivity as it moves offshore.”

But – just as we noted

2

days after the earthquake hit that the jet stream might

carry

radiation to the U.S. by wind – we are now warning that ocean currents might

carry more radiation to the at least some portions of the West Coast of North

America than is assumed.

Specifically, we

noted

more than a year ago:

The ocean currents head from Japan to the West Coast of the

U.S.

The floating debris will likely be carried by currents off of

Japan toward Washington, Oregon and California before turning toward Hawaii and

back again toward Asia, circulating in what is known as the North Pacific gyre,

said Curt Ebbesmeyer, a Seattle oceanographer who has spent decades tracking

flotsam.

***

“All this debris will find a way to reach the West coast or

stop in the Great Pacific Garbage Patch,” a swirling mass of concentrated marine

litter in the Pacific Ocean, said Luca Centurioni, a researcher at Scripps

Institution of Oceanography, UC San Diego.

CNN said that “the Hawaiian islands may get a new and

unwelcome addition in coming months — a giant new island of debris floating in

from Japan.” It relied in part on work done by the University of Hawaii’s

International Pacific Research Center,

which predicts that:

“In three years, the [debris] plume will reach the U.S. West

Coast, dumping debris on Californian beaches and the beaches of British

Columbia, Alaska, and Baja California. The debris will then drift into the

famous North Pacific Garbage Patch, where it will wander around and break into

smaller and smaller pieces. In five years, Hawaii shores can expect to see

another barrage of debris that is stronger and longer lastingthan the first one.

Much of the debris leaving the North Pacific Garbage Patch ends up on Hawaii’s

reefs and beaches.”

The debris mass, which appears as an island from the air,

contains cars, trucks, tractors, boats and entire houses floating in the current

heading toward the U.S. and Canada, according to ABC News.

The bulk of the debris will likely not be radioactive, as it

was presumably washed out to sea during the initial tsunami – before much

radioactivity had leaked. But this shows the power of the currents from Japan to

the West Coast.

An animated graphic from the University of

Hawaii’s

International Pacific

Research Center shows the projected dispersion of debris from Japan:

Indeed, an

island

of Japanese debris the size of California is hitting the West Coast of North

America … and some of it

is

radioactive.

In addition to radioactive debris, MIT says

that

seawater which is itself radioactive may begin hitting

the West Coast within 5 years. Given that the debris is hitting faster than

predicted, it is possible that the radioactive seawater will as well.

And the Congressional Research Service

admitted:

However, there remains the slight potential for a

relatively narrow corridor of highly contaminated water leading away

from Japan …

***

Transport by ocean currents is much slower, and additional

radiation from this source might eventually also be detected in North Pacific

waters under U.S. jurisdiction, even months after its release. Regardless of

slow ocean transport, the long half-life of radioactive cesium isotopes means

that radioactive contaminants could remain a valid concern

for

ears.

Indeed, nuclear expert Robert Alvarez –

senior policy adviser to the Energy Department’s secretary and deputy assistant

secretary for national security and the environment from 1993 to 1999 –

wrote yesterday:

According to a previously secret 1955 memo from the U.S. Atomic

Energy Commission regarding concerns of the British government over contaminated

tuna,

“dissipation of radioactive fall-out in ocean waters is not a

gradual spreading out of the activity from the region with the highest

concentration to uncontaminated regions, but that in all probability

the process results in scattered

pockets and streams of higher

radioactive materials in the Pacific. We can speculate that tuna which

now show radioactivity from ingested materials [this is in 1955,

not

today] have been living, in or have passed through, such pockets; or have

been feeding on plant and animal life which has been exposed in those

areas.”

Because of the huge amounts of radioactive

water Tepco is dumping into the Pacific Ocean, and the fact that the current

pushes waters from Japan to the West Coast of North America, at least some of

these radioactive “streams” or “hot spots” will likely end up impacting the West

Coast.

No comments:

Post a Comment